Henry Dadswell (1894-1978), a bush carpenter, returned from the battlefields of Europe on 5th April 1919 and was discharged from the Australian Army in Melbourne on 2nd July 1919. He had served overseas for more than three years as a signaller.

He later successfully applied for land at Red Cliffs in north west Victoria and as a soldier settler spent 50 years growing grapes and other fruit.

In 1927, he and Jessie Smiley (1908-1981) married at East St Kilda Congregational Church, Melbourne when Henry was aged 32 and Jessie was 19. They had met when Jessie was visiting her sister Lorna (nee Smiley) Weir who at that time was in the Mildura district. This is the second part of the early Red Cliffs experiences. The first instalment can be found here.

Jessie said that on their honeymoon, they had stayed at Horsham on their way home to Red Cliffs. They then travelled from Hopetoun by car to catch the Mildura train at Lascelles. "It was a terrible road, just sand. We then had to wait for the train, and I remember lying down on the seat on the platform early in the morning, I thought the train would never come.

"We had our first breakfast with Dick and Mary Spooner (Block 67c), who were our first good neighbours, and afterwards we were always friends with them."

Henry could recall that the house (built by himself and his father) had been let for about 12 months to people named Smith. The arrangement was they were to move out before Henry and Jessie arrived, and to leave the house clean. But the Dadswells arrived to find the yard littered with paper, and the house looking "an absolute shambles. I was terribly disgusted at bringing a woman home to such a mess."

Jessie could also remember arriving "home" on the train. There was a "tin kettling" as a welcome from other settlers. "But as we didn't have any drink they used to nip out of the house from time to time. Mrs Dewbury (Block 67) brought down their little gramophone and we had music. I don't think we had any dancing, it was such a small room."

Henry had a motorbike and the side car carried Jessie and their first-born child Marion until the birth of the second child, Gladys and then "it became a bit of a crowd. We then got a horse and jinker. We also had one of the first wireless sets (a large battery-operated radio), in the district. Two or three came one day - Monty Williams (Block 65), Charlie Richardson (Block 78a) - to hear the Melbourne Cup, and the darn thing wouldn't go. They were all sitting around to hear the race but I don't think they got to hear much that year."

Social life included tennis with Mary Spooner and others at Stewart and on occasions at Yatpool when Marion was a baby, travelling there on Mr Gange's old truck with the players sitting on sweat boxes on the back. Mr Gange had a large family and they all came, and all were hanging on for dear life. "Of course all the children tucked into the afternoon tea and we had a good day."

Social life also included dances with the couple taking the baby Marion in her pram. The couple would also go to dances at Yatpool and Carwarp; the roads were rough and sometimes even still had stumps of wood in them. The hall floors would be slippery to help the dancers.

Pictured above: Henry and Jessie Dadswell with their first-born child, Marion.

Below: Henry Dadswell and motorcycle. In sidecar, Charlie Richardson, Bonny Nolan (left) and Marion Dadswell.

Henry recalled the dances at Yatpool were well attended. One chap would take "sly grog" and one night an argument started. "I walked out of the hall and next thing I saw men going in all directions, as fast as they could run. I looked round to see the chap who had been selling the sly grog waving a pistol around and shouting 'I'll take on the lot of you.' I told him I wasn't part of this argument, that I didn't even see him, and I went back inside."

A "very flash" couple arrived at the Yatpool dance one night and passed some very disparaging remarks. The hall was unlined and rather rough but quite good for the country, and it had a wonderful floor. It was highly polished and you had to be very careful how you walked on it or you would slip over - your feet would just slide from under you. After he looked around, the visitor remarked "that they might as well have a dance since they had come all this way." But they both slid across the floor, hitting the floor hard, and everybody clapped them. They did look sheepish.

A "very flash" couple arrived at the Yatpool dance one night and passed some very disparaging remarks. The hall was unlined and rather rough but quite good for the country, and it had a wonderful floor. It was highly polished and you had to be very careful how you walked on it or you would slip over - your feet would just slide from under you. After he looked around, the visitor remarked "that they might as well have a dance since they had come all this way." But they both slid across the floor, hitting the floor hard, and everybody clapped them. They did look sheepish.

On another occasion a chap looked at this big, stout woman and made some remark about "how will I get round with this". She just picked him up, under his arms, and twirled around. He sailed round and round until she stopped and put him back on his feet. It certainly took the grin off his face.

At Nursery Ridge there was an old wool shed that was used for a recreation hall, and George Christian, the Methodist minister in Mildura, decided he would hold services there on a Sunday. He would get up in one corner, while in other parts of the hall fellas would be playing two-up, playing cards, using all kinds of language, and only a few would listen to George. They got so rough one day that George called them a lot of heathens, and said he would not come again.

During the week, two of the chaps got together to go into Mildura to see George and asked him to come again. They said they would make sure he got a good hearing. He agreed to try once more, but would not return again if things got bad. A few of the chaps were chatted up before the service, and things were fairly quiet. As others came into the hall, they had their hats knocked off, told to sit down and be quiet - "this is George's hour." There were some startled looks but they did as they were told.

The Church of England was the first church to be built. The Rev Norman Fettell came up and there were only pine stumps over the town where trees had been cut down. He had his suitcase and was sitting on one of the stumps when someone came up and introduced himself. They had a working bee the next day and erected the church, complete, in one day. It was a small church and the first in Red Cliffs.

One neighbour was Harry Pledge (block 53) and the families would visit one another.

Henry had eight years "batching" before his marriage with Jessie and he would help around the house which had a wood-burning stove and a tub outside for washing. Big tanks provided water. Eventually Henry's father came and they built an outside laundry which was used for washing and where there was also a separator for separating cream from the cow's milk.

A Coolgardie safe in the yard was used to keep food cool, and while that worked it was a lot better when they eventually got an ice chest. Over time, they got a sink in the kitchen.

The year 1927 was momentous. They had their first big frost which damaged vines, and this was followed by a severe hail storm which meant there was practically no crop to be harvested in 1928.

Ciss Weir (block 252) told the couple she overheard "old Jack Humphreys" (block 71) talking about Henry: "You should see a neighbour of ours; he's lost all his sultanas, nearly all his gordos, and he's just got married!"

Up until this time, fruit had been bringing in good prices, at 55 pounds a ton, with hardly any taxes and wages only 3 pounds a week. Because of the good prices, the Australians were not the only ones planting up, and additional acreages in the US, Turkey and Greece all came into bearing around this time, and the glut meant you could hardly give the fruit away.

Henry said he didn't know much about harvesting at first. He put in "a bit of a hot dip" and bought some hessian to lay the grapes on. It cost him 9 pounds a ton to harvest what gordos he got that year, and he was paid 8 pounds for them.

It was hard times all around. He said that to get a bit of money, people on farms around Yatpool would load up a ton truck, as high as they could, with mallee roots. They would go around the soldier settlers and would give a load for one pound. To get the mallee roots out, onto a truck and delivered, was well worth the one pound for the settlers.

Block 65a always had a wood heap, where any burnable wood was dumped. At any time of year, wood would be used in the fuel stove in the kitchen, and wood chips and bark would be burned in the chip heater which heated water for the bath or shower. In winter time, mallee roots were the favourite for burning in the lounge room, as they were slow burning and produced good heat. The disadvantage was that they were "cows to split" when they had to be chopped into useable-sized blocks.

The difficulties of the early years were compounded by the Depression times. Henry in 1977 recalled some aspects:

"And then (about 1929) labour costs went up to 4 to 5 pounds a week, and they asked the Arbitration judge if he would exempt the Sunraysia district from having to pay award wages while they tried to reorganise the industry.

"But he said no. He said he knew we couldn't pay, but rather than lower the wage he'd rather see the industry go out of existence. So we had to struggle on. We managed to get a better price the following year, but for several years we were practically working for not even wages.

"Some people had said to me I was mad to have a block, because even in the good years I would only ever get wages, and that didn't take into account the years when hail or frost would wipe out the crop. But as the Depression hit harder, two of those people told me how lucky I was to have a block, as they could not even get work. In those years, you might have up to a dozen people a day calling in looking for work.

"One chap came along wanting work, and he offered to finish putting in an underground tank. He asked for a "couple of bob" (two shillings, the equivalent of 20 cents in decimal money) for some food for that night. Next day when I saw him, he was back at work but was staggering around. Eventually I realised he had not had anything to eat. I asked him about it, and he said he and his friend had not eaten at all the previous day, and they had spent the 2/- on bread and things, but they were so hungry they had eaten it all that night. So there was nothing for breakfast. So we got him a meal. He was a 'bonzer' worker, and later when Arthur Barber (block 72) wanted a hand, this chap worked for him. He returned for work for three or four years after that first meeting.

"The Depression was an awful time. I had people here who had been at university and couldn't get a job, people who had been in jail, bricklayers, carpenters, tradesmen of all kinds, and all were glad to get even a few weeks work.

"The Water Commission offices included "old Bromfield" (S. P. Bromfield) who was at Red Cliffs for many years, Ray McConchie, Drummond and Webb who was in charge of the pumping station.

"The area also had its characters. One was Mrs Campbell, who lived close by in a humpy by the Murray River. She would walk the three miles (five kilometres) into Red Cliffs and after a few drinks would stagger home. On one occasion she poured a kettle of boiling water over her leg and was badly scalded, and the doctor saw her in hospital. He told her they had to fix the leg up, as "it wouldn't do" to give her a wooden leg. When she asked what he meant, he said the white ants might give her some problems!

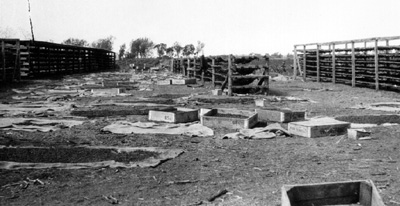

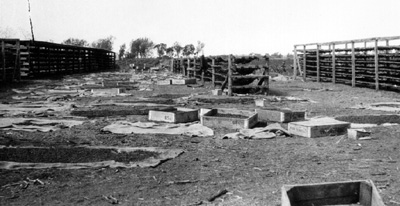

Pictured above: Drying grapes at Red Cliffs. "Mrs Campbell had a friend, Bob the fisherman, who used to help her home sometimes. She would lean on his bike as they made their way home from Red Cliffs. Bob was another who was kind to everyone except himself."

Next to the nearby Red Cliffs East school was Mr and Mrs Dewbury, and they had a tuck shop-type store, and she was always very good with the school children. Henry could remember coming past the Dewbury block one day when Bert Dewbury was driving the horses and Mrs Dewbury was on the plough. She also chopped the wood for the fire and did much of the work around the place. Bert used to irrigate the block by letting the water on, and walking to the road. If the water was up to a certain level over the road, he would cut it off; if not, he would just walk back to the house and let it run. So we couldn't get along that road while he was watering.

Close friends of Jessie and Henry were Jack and Jean Edey, who developed land on the Murray at Karadoc. Jack published an autobiography, From Lone Pine to Murray Pine in 1981, and recalled one aspect that early Red Cliffs settlers were well familiar with:

"In the late 1930s, we ran into another series of droughts with high winds and dust storms. Frequently the dust storms were so intense that lamps had to be lit in the middle of the day, providing an eerie light. Red Cliffs still has a record of one dust storm which lingered over the town for a few days like a huge black cloud."

Henry recalled there were several storms where the dust was so thick they had to light lamps in the afternoon. Many Red Cliffs settlers were English, and next door was Arthur Barber and his wife. Mrs Barber was a clean, fussy sort, and after one dust storm she set to work and cleaned the house. She had just finished when a second storm hit. She set to work again and cleaned up and had just about finished when a "willy willy" came by and hit the house. "I went up for some reason and she was sitting there, crying. That was what a lot of the women had to put up with in the early days."

With the outbreak of World War Two, Henry joined the Volunteer Defence Corps of the 2nd AIF, and was attached to the Portsea, Victoria, garrison. Minutes of Red Cliffs East School Council for 10th April 1942 recorded "In the unavoidable absence of Mr Dadswell for whom an apology was received, Mr Hogan was voted to the chair".

From 29th July 1942, Henry was on part-time duties until his discharge on 17th September 1945. It was during the war years that he became involved with the scouting movement, as a "fill-in" leader. As well, both he and Jessie became members of the parent committee for the 2nd Red Cliffs Group.

As scout master, Henry took the weekly scout meetings, encouraged physical fitness, drilled scouts in both morse code and semaphore signalling (in which he was still expert), and led scouts at their camps and helped with the building of the scout hall at Stewart. His positions included scout master, group scout master, district commissioner and acting county commissioner.

The scouting movement, 20 years later, recognised the "fill-in leader" with the award of the Medal of Merit in recognition of his good services to the Scout movement.

"Now (in 1977), there are less than a dozen of the old boys here in Red Cliffs and we are rather shaky and in our 80s."

The couple, who raised five children, lived on Block 65a for fifty years before moving into the township of Red Cliffs. Henry died in 1978 and Jessie in 1981. Both are buried at Mt Cole Cemetery, close to Henry's birthplace.

This is the second part of Red Cliffs recollections. The first can be found at part 1. This instalment compiled December 2023 Return to Family Stories Index Page

|

A "very flash" couple arrived at the Yatpool dance one night and passed some very disparaging remarks. The hall was unlined and rather rough but quite good for the country, and it had a wonderful floor. It was highly polished and you had to be very careful how you walked on it or you would slip over - your feet would just slide from under you. After he looked around, the visitor remarked "that they might as well have a dance since they had come all this way." But they both slid across the floor, hitting the floor hard, and everybody clapped them. They did look sheepish.

A "very flash" couple arrived at the Yatpool dance one night and passed some very disparaging remarks. The hall was unlined and rather rough but quite good for the country, and it had a wonderful floor. It was highly polished and you had to be very careful how you walked on it or you would slip over - your feet would just slide from under you. After he looked around, the visitor remarked "that they might as well have a dance since they had come all this way." But they both slid across the floor, hitting the floor hard, and everybody clapped them. They did look sheepish.