Members of the extended Dadswell family were shocked in 1934 when one of their own was murdered in suburban Melbourne. Almost as shocking was the news 11 years later that the alleged murderer was living close to some of the family in the small town of Red Cliffs, in northwest Victoria.

The story of the life and death of Tom Norwood has brought to light some extraordinary coincidences along with a tragic story.

Herbert Thomas (Tom) Norwood was born on 14 May 1899, the son of Helena Matilda (Dadswell) and Sidney Herbert Norwood.

Helena (also known as 'Tilda) and Sidney had married at Deniliquin, New South Wales, in 1891 and were living there, running the White Lion Hotel in End Street (now Maher Street) when Tom was born.

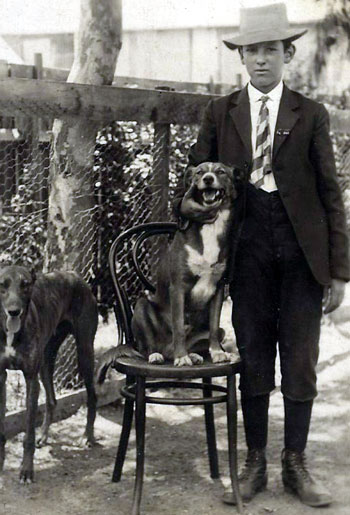

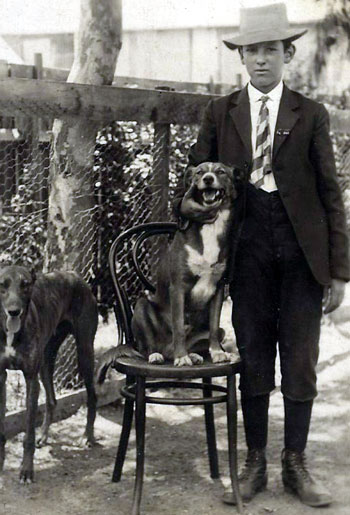

Tom's sister Fran Souter (1894-1984), who lived at Ballan, Victoria, for many years, could recall that Tom (pictured), when about 4 years old, almost drowned one Sunday afternoon when he walked along a plank and fell into water.

Fran could also recall that Tom, then aged 6, travelled with his father and two brothers (Sid and Charles) by horse and jinker for 170 kilometres when the family shifted from Deniliquin to another hotel at Shelbourne, near Bendigo, Victoria.

In 1916, at the age of 17, Tom Norwood joined the Victorian Railways. His first appointment was as a 'youth' at Richmond station.

Three years later, on 3 June 1919, his cousin Henry William Dadswell (1894 - 1978), who had just been discharged from the Army following war service overseas, recorded in his diary a meeting with his younger Norwood cousin.

Henry had been travelling around Victoria meeting relatives and friends following his time overseas, and on this occasion was staying with a Mrs Bithell and family at Castlemaine. He records that in the afternoon he drove a Miss Sandon to Donolly and "brought Tom Norwood back."

Tom's railway service took him to various parts of Victoria - Raywood, Swan Hill, Orbost, Pakenham, Nyora, Branxholme and Nar Nar Goon.

In one of those strange coincidences, Tom can be remembered at Nar Nar Goon by Ian Robinson (born 1922 and who in 1953 married Gladys (Gaye) Dadswell, a daughter of Henry Dadswell).

The Robinsons owned a general store at Nar Nar Goon in the 1930s and one of Ian's jobs - at the age of about nine - was to collect newspapers carried by train from Melbourne, and to then deliver them around the village. He can recall Tom working at the railway station during this time, and his subsequent promotion to assistant station master at Carnegie in Melbourne.

Not long before this promotion, on 14 June 1930, Tom - then aged 30 - married a nurse, Veronica Jane Pickett, aged 29, the third of six children of Joseph William John and Jane (Cozens) Pickett, at St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne. One of Veronica's sister, Diana (also known as Dinah) was a witness at the ceremony.

The move to Carnegie

About a year later they had a daughter, Betty, and the family lived at 67 Elliott Avenue, Carnegie, with Tom working a short walk away at the Carnegie station.

The move to Melbourne was a fateful one. On the evening of 1 October 1934, as Tom as tallying up the day's cash takings, a man with a revolver appeared at the parcels office window and demanded the takings.

The Argus reported on 2 October 1934:

Callously shot in the back by an armed man, Henry (sic) Thomas Norwood aged 36 years, assistant stationmaster at Carnegie, was killed in the booking office of the station last night.

Entering the parcels office about 10.20pm, a young man armed with a revolver called upon Norwood to hand over the cash in the office.

Norwood ran to the telephone to give the alarm. Two shots were fired by the man and the bullets lodged in Norwood's back. It was found later that Norwood, after he had been mortally wounded, telephoned to the railway control-room at Flinders street and said "I am shot, send for the police".

The man who fired the shots ran from the office and escaped along Railway parade. Several persons who were waiting for a train saw the man. Norwood died a few minutes after the shooting.

And in the same report:

Apparently the "hold-up" was carefully planned, as yesterday was the first day of the month and an unusually large amount of money had been received from persons who had purchased monthly tickets.

The man entered the station when Francis Morrissey, a young porter, was on the Oakleigh side of the platform, "clearing" the 10.19pm train to Dandenong.

Norwood, the only other railway employee in the station, was counting cash amounting to £147 [$294], which was to be sent away on the "cash train," due at 10.55pm.

The police believe that the man, who was apparently alone, entered the parcels office which adjoins the booking office, and that Norwood went to the counter expecting to answer an inquiry about a parcel. Pointing the revolver at Norwood, the police believe the man demanded money. Norwood ran to the telephone on the opposite side of the booking office.

Two shots were fired, both of which struck Norwood in the back. As Norwood collapsed, the man ran out of the parcels office without taking any of the money.

Police told journalists that Frank Morrissey, a youth porter, heard a 'report' as the 10.19 train was leaving the station but he believed that it was the noise made by the shutting of a carriage door. Then two young men on the other platform called "Come over here, there's been a hold-up".

Morrissey ran across the line and tried to break open the door which Tom Norwood had locked while he was counting the cash. In response to Morrissey's call for help, signalman Roy Haddon ran from the signalbox and smashed a glass pane in the door. He then turned the lock and entered the office. Tom Norwood was lying on his back moaning but soon after died without speaking.

The following day (3 October 1934), The Argus continued its report on the shooting. Part of its coverage stated:

When a post-mortem examination of Mr Norwood's body was made by the Government pathologist (Dr C. H. Mollison) yesterday, it was revealed that the bullets, fired from a .32 calibre revolver, had entered the body 7½ inches apart in the back. They had been fired at close range, and after striking Mr Norwood in the back, had lodged in the chest. Mr Norwood died as the result of internal haemorrhage.

In their reconstruction of the shooting, detectives said that Tom Norwood — who would not normally have worked that evening shift* — was shot as he was trying to avoid the thief and leave the office. If he had been able to reach a partition dividing the parcels office from the booking office he would have been safely out of range of the gunman's revolver and would have been able to summon assistance or reach his own revolver.

[* The Carnegie stationmaster, John (Jack) Carrolan, wanted to attend a family function that day and so the two swapped shifts.]

The murderer was believed to have tried to gain entry to the office so he could access the money and still keep the assistant stationmaster covered with his revolver. When he realised that the railwayman would probably telephone for urgent help, he shot him in the back.

Police said Tom Norwood was able to phone the railway control room at Flinders Street gasped out the message, "I am shot. Send for the police."

He died a few minutes later, before a doctor could be summoned.

Police also said they thought that while he was lying wounded on the floor of the office, the would-be thief tried to gain entry, as the mesh grille through which the shots were fired were found to be damaged. The intruder had evidently pulled at the grille and managed to lever one corner loose but had ran off soon after the shooting.

Police searched the area for a revolver but it appears this was not found.

A funeral service was held at the family home in Elliott Avenue and at Fawkner Cemetery, in Melbourne's north. An estimated 180 uniformed railwaymen marched in front of the hearse as it moved along Sydney Road, while at the cemetery the coffin was carried by six of Tom Norwood's colleagues.

Late in October, Tasmanian Police arrested a man on behalf of Victorian Police. It was alleged he had absconded on bail on numerous occasions and was believed to be in Melbourne at the time of the murder. However, no charges were laid relating to the shooting.

In the following March (1935), the Coroner, Mr Hauser, heard descriptions of the person alleged to have been the gunman, but he recorded a finding that Tom Norwood had been murdered by a person unknown.

Police files into the shooting are not available at this time, and the investigation appears to have not turned up any solid developments for 11 years.

Arrest at Red Cliffs

But a startling announcement was made in The Herald on 13 June 1945: an arrest had been made at Red Cliffs, the small returned soldiers settlement in northwest Victoria where the family of Henry Dadswell lived.

The news that the accused man had been living in the same locality astounded the Dadswell family. One family member can recall that the accused man was said to have been the driver of the horse-drawn cart which delivered bread to Red Cliffs vineyards, including the one owned by the Dadswells.

The news of the arrest featured in a number of newspapers which reported on a preliminary hearing in Malvern, Melbourne, when Thomas Croft, a 39-year-old mechanic of Red Cliffs, was charged with the murder.

According to The Argus of June 14, one of the witnesses at the hearing said she had identified the accused man from a police line-up, and he was the man she had seen at Carnegie station on the night of the shooting.

On the basis of witness reports and police evidence, Thomas Croft was committed to stand trial later in the year.

The murder trial began on August 7 with the Prosecution saying the trial would hear:

- witness reports which placed Thomas Croft at the station on the night of the killing;

- evidence of conversations between Thomas Croft and two witnesses, where the accused man was alleged to have described the shooting;

- a written statement made to police by Thomas Croft admitting he was at the railway station but took the pistol only to bluff anyone who might see him, that while he was trying to get his hand under the grille covering the window the man in the office had rushed to the door, and in trying to pull the pistol back it had caught in the grille and gone off several times.

Court records from this time are not yet available but one of the main witnesses was Kenneth O'Connell who said he had known Thomas Croft both before and during the time both he and Thomas Croft had been in jail in NSW. O'Connell said Thomas Croft had described to him the shooting and escaping from Melbourne by ship and throwing the pistol into the sea on the voyage to Sydney.

At times he had said the shooting was deliberate to prevent the phone call. At other times he said he did not intend to shoot Tom Norwood — when he was trying to reach the cash bag the gun had caught in the grille and had gone off.

Following the police and witness evidence, Thomas Croft did not take the witness stand but made an unsworn statement from the dock, and denied he was at the station on the day of the murder.

He said the only time he was in Melbourne in 1934 was about the middle of the year when he had tried to effect a reconciliation with his wife (the shooting was in October of that year).

He said he had been questioned repeatedly by police over a number of days, had been hand-cuffed to a chair, treated violently and threatened. He said he had signed a statement admitting the shooting only because he could not stand the treatment any longer.

At the end of the trial, the jury retired for six hours but could not agree on a verdict. In the absence of either a conviction or an acquittal, Thomas Croft was required to face a further trial the following month. In September 1934, a new trial proceeded but again the jury could not agree on a verdict. A further trial was ordered for November.

For a third time a jury could not agree on a verdict and a fourth trial was ordered for December, but before the trial began the prosecution announced there would be a nolle prosequi — a stay of proceedings which brought the prosecution to a halt.

No other reports of charges relating to the death of Tom Norwood have been found, so it appears that no one was found guilty of the murder. But there were other dramatic developments in the life of Thomas Croft (see below).

Today, thousands of commuters pass through the railway station at Carnegie, but probably none are aware of the tragedy back in 1934. Today the station has no staff and no memorial records the shooting.

Tom's widow Vera moved from their Carnegie home and for about 15 years lived in the nearby suburb of Caulfield, at 55 Filbert Street. Later she shifted to number 49 in the same street, and was still living there in the mid-1960s. During some of this time, she was associated with the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind. It was in the 1950s that her daughter Betty married.

- Information compiled May 2008, updated October 2008 Related information

The Turbulent Life of Thomas Croft

Norwood family members

Return to Family Stories Index Page

|